Using the experience of previous generations, raising their achievements to a new qualitative level, the development of scientific and technical thought is moving upward in a spiral. It is no coincidence that inventors, creating more and more advanced machines, often return to the experience of their predecessors - in their searches they rely on the designs of bygone years.

A characteristic example of such continuity is the history of crews driven by the muscular strength of man. We have already repeatedly told about one of the modern branches of their descendants - velomobiles ("M-K", 1976, No. 7; 1979, No. 11, 12). It is no less interesting to look back and trace how the idea of "muscular" transport was born and developed in the distant and recent past.

Going deep into the history of technology, we will see a certain paradox that lives for centuries and has survived to this day. It became noticeable at a time when carriages and carts drawn by four-legged helpers of man were already scurrying along the paved and unpaved roads of antiquity. For more than one century, horses, oxen, mules have served as a living drive to the wagon. But grew transport needs, and the man began to dream of creating crews capable of taking more cargo and develop high speeds. A car appeared, which was preceded by the invention of the engine: first steam, then internal combustion, electric motor. But that was later. This still had to come. Through the times when fun with "fiery machines" could end at the stake of the Inquisition. And even earlier, when naive, but ingenious ways were invented for the movement of the wagon, which today seem primitive, and sometimes even curious. However, let us not judge the ancestors too harshly. Indeed, in almost every one of those ancient structures, a prototype of some detail was already guessed. modern machines: transmission, steering, brakes. Many finds, having undergone all sorts of improvements, are firmly established in modern transport.

The principle of driving a trolley by the muscular strength of a person sitting in it turned out to be tenacious. It became especially tempting at a time when it was already seen in application to asphalt roads. Not just “horseless carriages”, but fast and powerful cars, airplanes took off into the sky, now spaceships go to distant planets. But two eternal dreams are alive in a person: to fly like a bird and to push some light carriage with the power of one's own muscles. When did it originate, in what ancient times? Watch mechanisms appeared, water turned the wheels of mills and pumps, people already managed well with sails. But ... the energy of falling water cannot be adapted to a moving wagon, the springs are weak and unreliable, and the sails are suitable only with a good wind, and even then mostly on the water. And I wanted so much not to depend on anything ...

One of the first, probably, attempts to implement the idea of using own strength to set a light wagon in motion belongs to the Augsburg carpenter Walter Goltan. It was he who, at the beginning of the 15th century, drove into the narrow streets of his town on an unusual four-wheeled structure, which turned out to be a self-propelled muscular carriage. Pulling the endless rope, the rider set two drums in rotation. The lower one, with longitudinal rails, made the gear wheel, rigidly mounted on rear axle. Needless to say, the speed of the stroller was no higher than that of a pedestrian. But what about the steering wheel? Well, in those days, the problem of rotation did not bother the inventors yet. If it was necessary to change the direction of movement, the rider got out of the cart and, raising the front end, aimed the cart in the right direction.

The crew of Goltana was single. But someone Auguste from Memmingen in 1447 built a giant (even by today's concepts) self-propelled machine on four huge wheels. She could carry several dozen people at once. Of course, history is silent about speed, but this was not the main thing in those days. More importantly, the car was moving! By means of ingenious devices, levers, rollers, gates inside the carriage, people rotated all four wheels of the wagon. The designer took care in such a way that in the event of one of the wheels getting stuck in the pothole, the others could pull the car to flat road. Here it is, the prototype of modern all-wheel drive all-terrain vehicles!

On the principle of using muscular strength, other self-propelled carriages of the Middle Ages were also created. In 1459, an unusual carriage took part in the triumphal procession of the German emperor Maximilian I. It was a six-meter hoop-wheel, inside of which the reigning persons were located. The carriage-wheel moved as a result of the fact that the servants stepped over its inner surface, and the direction of movement was regulated with a long lever by a servant walking nearby. At the same time, a wooden four-wheeled carriage appeared, driven by servants walking next to and behind it, who, with the help of levers, rotated the shafts and flywheels mounted on the body. Only sketches of such machines have come down to us: there is no other reliable data on their existence. These wagons were designed, in particular, by the famous artist Albrecht Dürer, who left us several drawings of his inventions.

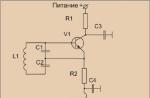

In 1685, the famous Nuremberg watchmaker Stefan Farfleur broke his leg. This seemingly insignificant, purely personal event served as an impetus ... to further development and the improvement of a self-propelled carriage - so far only in the form of a muscular cart. Farfleur was not very pleased with the prospect of using crutches or staying at home. He built a small three-wheeled carriage, on which "he himself could go to the church without anyone's help." It is clear that here the speed was not so hot. In the carriage, he used the principle of his own clockwork. Only the strength of the springs and weights was replaced by their own muscles. Turning special handles, Farfleur through a system of gears set in rotation front wheel. Modern motorized carriages and front-wheel drive cars echo this scheme.

Our compatriots also contributed to the development of "self-running cars". In 1752, the first such carriage was built in Russia, driven by a complex system of levers and pedals, which were controlled by two lackeys standing on the heels. Its creator is Leonty Lukyanovich Shamshurenkov, a peasant of the Nizhny Novgorod province, a wonderful Russian self-taught inventor, endowed with great imagination and ingenuity. On June 21, 1751, he sent a request to the Senate Commission in Moscow for permission and financial assistance to “... make a self-running carriage that can run without a horse. He, Leonty, can truly make such a carriage, with machines invented by him, on four wheels, with tools so that it will run without a horse, only it will be driven through the tools by two people standing on the same carriage, except for the idle people sitting in it. , but it will run through some long distance and not only in a flat location, but also to the mountain, there will be a place where it is not a very cool place, and also the stroller can be made, of course, in three months with all perfection, and for approbation for making the first such stroller, he needs no money from the treasury more than 30 rubles ... ".

Only a year later in St. Petersburg, Shamshurenkov "with all haste" began to implement his plan. And on November 1, 1752, the stroller was completely ready for testing. No drawings, drawings, or even a sensible description of this self-propelled vehicle with a muscular drive have survived to this day. According to a few documents, it can be judged that the carriage was four-wheeled, closed and resembled a carriage - not bulky, but rather light and durable. Two people with the help of pedals rotated the rear wheels and controlled its movement. The crew carried at least two passengers.

A year later, having completed the work, the 60-year-old inventor, still full of energy and energy, again writes to St. Petersburg: “... and now I can still make a sleigh for testing that will go without horses in winter, and for testing they can go in summer with need ... And although the carriage I made before is in operation, but only it’s not so fast, and if it’s still allowed, then I can make that former dressing room and move faster and more firmly with skill. But these proposals were refused, and all further requests were in vain. Soon, the inventor and his "self-running wheelchair" were forgotten, and their fate is unknown.

Another talented Russian mechanic - Ivan Petrovich Kulibin - worked on the original carriage for several years and finished it in 1791. All mechanics outwardly seem simple, but the eye of a modern designer will immediately distinguish whole line even in modern times brilliant solutions. Kulibin made the crew three-wheeled, for one passenger. The wooden frame consisted of two longitudinal bars connected by crossbars. A turntable with a single steering wheel, controlled by rods and levers, was attached to it in front. At the rear, two other wheels of increased diameter were installed on the frame. The pedals - or "shoes", according to Kulibin - were alternately pressed by a man standing on his heels. By means of rods and ratchet mechanisms, he drove a heavy horizontal flywheel, which facilitated the work of a person on the pedals and softened the course of the machine. The rotation of the vertical shaft of the flywheel was transmitted through simplified gears on the right rear wheel.

An interesting design of the mechanism for transmitting torque to driving wheel, which became the prototype of modern step boxes gears. On the axis of the ear was a drum with three toothed rims of different diameters and with an unequal number of teeth. The gear of the longitudinal shaft, moving along the diameter of the drum, could be connected to any crown, changing gear ratio, and hence the speed of rotation of the wheels and the applied force.

The "scooter" also had a freewheel mechanism, which gave a person the opportunity to rest, using the inertia of the pose and flywheel. And one more remarkable technical foresight can be found in Kulibin's carriage: the axles of the wheels rolled on three special rollers. This device is the forerunner of the modern roller bearing! In short, the manual transmission and bearings on this bogie were designed and used half a century before they appeared in France and England. You can get a closer look at the design of the "scooter" in the department automotive technology Polytechnic Museum in Moscow, where its current model is kept.

And yet, the improvements introduced by Kulibin into the design of the stroller could not turn it into a full-fledged self-propelled carriage, the living engine was too weak and unreliable. Similar attempts to create "muscular" transport were made more than once in the 18th century and abroad. However, all such machines remained only an original toy at court. It is known that in England a single-seat wagon similar to the Kulibino, only four-wheeled, was built by John Bevers.

In a word, "self-running cars" turned out to be unreliable and practically unacceptable. And yet they were the first steps towards satisfying the human desire to move faster. Of course, unfortunate inventors also appeared along this path, who proposed meaningless structures that were included in the fund of autobike curiosities. Here is one of these ideas: put oars-rakes on an ordinary wagon and push them off the ground. In another "stunning" device, it was supposed to use the principle of a squirrel wheel, but with dogs. To do this, the front wheel of the wagon had to look like a drum, inside which the animals had to run. There was also an equally original project: they wanted to force the horse to press the pedals. But ... dogs and horses refused to perform such unusual duties for themselves, and these "promising crews" were stuck in place, lost in the annals of the history of technology.

But the same story took away all the more or less rational grains in muscle projects. Remember the flywheel on Kulibin's scooter. This idea was developed by the Hungarian Josef Horthy-Horvat, who in 1857 proposed a multi-seat omnibus, on the roof of which a huge flywheel was installed; the torque from it through the bevel gear and the shaft was transmitted to the rear wheels of the crew. The duties of the "driver" were only to spin it. Three years later, the Russian engineer V.I. Shubersky developed a flywheel project, which also uses the energy of a rotating flywheel. And in 1905, the Englishman Lanchester patented the "flywheel car". One or two heavy flywheels with mechanical transmission turning the wheels of the car. Electric motors were used to accelerate the flywheels, but it could also be done manually.

And now, in our days, the energy crisis and hypodynamia, the dominance of cars in major cities, noise, gas pollution of the atmosphere forced to pay attention again to some "muscular" vehicles, once supplanted by powerful and compact engines. First of all, they should include bicycles, as well as carriages based on them - velomobiles set in motion by human muscles.

From the bicycle, the velomobile received a simple chain drive, light wheels; from the car - transmission, bodywork, lighting system, the beginnings of comfort. The design of all nodes is aimed at fulfilling the main condition - the maximum facilitation of the driver's work. This is how the coil of the spiral of development of muscular Vehicle that began five centuries ago.

Today, on the streets of Tokyo and Amsterdam, Paris and Milan - many cities in the world, no, no, yes, non-motorized cars for one or two or even a dozen or two people will flash in a dense stream of transport. In them, everyone is busy: pedaling or pressing the drive levers. How can a car keep up - of course, not in speed, but in efficiency, maneuverability, harmlessness for environment: how many advantages at once! And to turn the pedals to the current city dweller, suffering from inactivity, is by no means useful.

Non-motorized cars are built in the most various options: from nimble single-seat velomobiles to giant multi-seat "velobuses" - three-four-wheeled carriages without a body with a common transmission to the rear drive wheels. So far, many of them have been created out of self-promotion or a desire to surprise compatriots, attract attention, cause a sensation.

One of the first projects of a small bicycle bus, for 21 people, was proposed in 1949 by the Frenchman Pierre-Albert Farsa. But the Dane Tag Krogshav clearly overtook all competitors, having built a three-wheeled bike monster weighing more than 3 tons, designed for 35 (!) people. It took 78 old bicycles, 35 saddles, 70 pedals, three automotive wheel Only the length of 70 chain drives was more than 50 m! So far, Krogshave has found the only practical use for this monster in the fact that he occasionally rides local children on it.

We have already talked about light velomobiles built in our country: about the Kharkov crew "Vita" ("M-K", 1976, No. 7), the folding velomobile "Hummingbird" ("M-K", 1979, No. 12). Several velomobiles with streamlined bodies were created by students and employees of the Vilnius Engineering and Construction Institute. In the winter of 1981, the country's first muscle car competition even took place.

But, no matter how good velomobiles are, they still exist in single copies and have not become a noticeable phenomenon in traffic flows large cities. However, in Japan, where problems of traffic congestion and air pollution exhaust gases especially sharp, serial production of several types of non-motorized equipment has already begun: a light three-wheeled pedicard with a canopy and a more comfortable four-wheeled one. average speed they are low - 10-15 km / h, but this is quite enough for short trips. Such transport will be useful not only for personal use, but also for postmen, doctors of district clinics; for teaching young people the rules of the movement, application on the territory of large enterprises, farms, construction sites.

The velomobile is taking its first and so far unsteady steps today (despite its almost five hundred years of history!), but the huge advantages of simple and affordable transport determine its great future. There is still something to think about and work on for inventors in this ancient and, perhaps, at the same time, the youngest form of transport that does not need an engine that serves human health. And we hope that amateur designers, readers of our magazine, will contribute to this matter.

Noticed an error? Select it and click Ctrl+Enter to let us know.

Post navigation"The guy who invented the first wheel was an idiot, but the guy who invented the other three was a genius." Sid Caesar

One of the first images of a wagon

The ideas of many machines and mechanisms belong to the genius of Leonardo da Vinci (Leonardo da Vinci). Not without his participation and this time. Among the drawings of Leonardo, there was a project for a self-propelled cart. It had three wheels and was driven by a clockwork spring mechanism. The two rear wheels were independent of each other. Their rotation was carried out by a system of gears. For control, a fourth small wheel was provided, to which the steering wheel was attached.

It is assumed that Leonardo developed his self-propelled cart at the end of the 15th century, and it was planned to use it in the theater and at carnival processions. However, history decreed otherwise. The descendants of Leonardo's design can be seen anywhere, but not on the theater stage.

Reconstruction of Leonardo da Vinci's car

The next step towards the appearance of the automobile was the invention of the Jesuit missionary Ferdinand Verbiest. Around 1672, he designed the first steam-powered machine. It was a toy for the Chinese emperor with no practical use. Verbst's car was 65 cm long, not driven by a driver, and could not carry passengers.

The missionary's invention has little in common with the steam carts of the late 18th century, but the idea of a steam-powered machine belongs to him. It is not known for certain whether Verbst brought his project to life, however, a description and drawing of the car is in his book Astronomia Europea.

Drawing of a steam car by Ferdinand Verbst

The end of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries became the time steam engines. Verbst's idea of using steam to move a wagon was adopted by many inventors. Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot became the first creator of a workable steam car. In 1769 he designed an artillery tractor. The machine was driven by a 2 hp steam engine. At maximum load at 2.5 tons, the car could move at a speed of 4 km / h. But Cugno's invention had a serious drawback: every 15 minutes the water in the boiler had to be brought to a boil, and the steam supply was enough to cover only 250 meters. Therefore, the design proposed by him did not find practical application.

Artillery tractor Cugno, 1769

However, inventors continued to work on improving steam engines for cars. In the UK, they were developed by William Murdoch (William Murdoch) and Richard Trevithick (Richard Trevithick). In 1784 and 1801 respectively they introduced their steam carriages.

Many British designers have succeeded in building multi-seat self-propelled carriages. But the era of steam wagons in Britain was short-lived. The railway workers were afraid of competition and contributed to the adoption by Parliament of a law that greatly complicated the life of manufacturers and owners of the first cars. The situation changed only in 1896, when the world was conquered by the possibilities of internal combustion engines.

English steam bus, 1829

Russian inventors did not stand aside either. In 1791, Ivan Kulibin completed work on a "scooter cart". It had three wheels and was set in motion by pressing special pedals. Kulibin's design has more in common with velomobiles than with cars. However, the Russian inventor used in his "scooter cart" design solutions, without which it is impossible to imagine modern car: flywheel, brake, gearbox and bearings.

Kulibin's car did not find application, since government officials did not see in it the potential for further development and mass production. A steam cars appeared in Russia much later than in Europe and the USA. In 1830, in St. Petersburg, K. Yankevich, with two mechanics, developed a project for a steam self-propelled vehicle - a “quick-roller”, but it was never built. And only 30 years later, Amos Cherepanov invented a steam self-propelled tractor.

"Scooter cart" Ivan Kulibin, 1791

Steam engines did not take root well in cars. They were unreliable and dangerous, had big sizes. Therefore, the designers were looking for other sources of energy. Surprisingly, the idea to use electricity to move cars also belonged to a servant of God. In 1828, the Benedictine Ányos István Jedlik invented the first electric motor and put it on a miniature car model.

The idea was picked up by other designers. The first workable electric vehicles were assembled in the 30s and 40s of the 19th century. The pioneers can be considered the British Robert Anderson (Robert Anderson), the Scot Robert Davidson (Robert Davidson) and the American Thomas Davenport (Thomas Davenport). Their inventions could not boast of reliability and high speed movement. But over time, the design of electric vehicles improved, and their production increased. In 1899, a record was set - a car with an electric motor reached a speed of 100 km / h.

Thomas Parker's electric car, 1884

At the beginning of the 20th century, electric vehicles seriously competed with newcomers with internal combustion engines. During this period, they were produced in the United States several times more than cars with gasoline engines. The Detroit Electric Company was especially distinguished, which from 1907 to 1942 produced electric vehicles that were very popular with Americans. During the war period, the development and production of cars with electric motors practically ceased. The designers could not have imagined that the rapidly gaining popularity of cars with internal combustion engines in a hundred years would again fight for a place in the sun with electric cars.

Detroit Electric, 1916

In the second half of the 19th century, the most an important event for the automotive industry: was engine invented internal combustion. The first attempt to create it was made by the French designer Philippe Lebon. In 1801, he invented the internal combustion engine, powered by light gas. Unfortunately, work on it was not destined to continue, since 3 years after the creation of the prototype, Lebon died.

Following him, the Belgian mechanic Jean Étienne Lenoir and the German inventor August Otto were engaged in the development of internal combustion engines. The latter has been particularly successful. Although his engines did not have an electric spark plug, like Lenoir's, they were more productive and five times more economical. Therefore, the invention of the French gave way to the design of Otto. These first serial engines internal combustion used gas as fuel. Designers immediately appreciated the advantages of size and began to install them on cars. The first machine with a Lenoir engine was tested in 1860.

Lenoir's car, 1860

The inventors did not stop there and continued to search for the best fuel for their engines. Around 1870, the Austrian inventor Siegfried Marcus placed liquid engine on a cart, which was called "Marcus's first car." Later, the inventor created his second prototype. "Second car Marcus" had a more complex design. In 1872, American mechanical engineer George Brayton created a prototype engine that ran on kerosene. Later, he decided to use gasoline as fuel. But the designer ran into problems, the solution of which outstripped the invention of German engineers.

"Markus' Second Car"

It is believed that the first workable gasoline internal combustion engine was created in 1885 by the German engineer Gottlieb Daimler. It was tested on the world's first motorcycle and later installed on the crew. Creator of the first stock car With gasoline engine recognized by Karl Benz. But that's a completely different story...

SCOOTER

In 1791 Kulibin invented the scooter. She did not reach us - the author himself did not want this. And this, as we shall see, has its own explanation.

A scooter is not a bicycle, it is a crew, but for individual use. It is set in motion by the muscular strength of a person. The idea of creating such a crew originated a very long time ago. Historians of technology consider the ingenuous wheelchair of Roman children to be the prototype of the scooter. This is a horizontal narrow plank on two small wheels. A vertical stick is attached to it, which serves as both a support for the hand and a steering wheel. Roman children rode such carts, with one foot on the board and pushing off the ground with the other. Luckily for the kids, the carts haven't changed in the last two thousand years, and now kids are clattering down the sidewalks on them. It was here that the principle of using muscular strength for self-propulsion was applied for the first time. Then they already thought of scooters; after them and before the bike. The invention of all kinds of carriages set in motion by the muscular strength of the people themselves is extremely characteristic of the period preceding the introduction in transport mechanical motor. Most of these self-propelled carts proved to be practically unusable due to the discrepancy between the weight of the carriage and the relative weakness of the muscular strength of people, but two vehicles using this power - the bicycle and the railcar - came into practice.

"Kulibinsky lantern" with a mirror reflector.

Three-wheeled scooter Kulibin. Reconstruction of Rostovtsev.

G. R. Derzhavin. From a portrait by Tonchi.

Scooters or carts, which were driven by human muscles, were invented back in the Renaissance. And perhaps even earlier. Roger Bacon in 1257 expressed an opinion about the possibility of arranging such a cart. In the 16th century, mechanical carts were known that served military purposes. These are, if you like, the ancestors of modern armored vehicles and tanks. Even the names of famous craftsmen for the manufacture of such carts have survived to our time. In England, as early as the 17th century, “automatic carriages” were patented, although their design is unknown to us. Isaac Newton in his youth invented some kind of scooter, but it could only move at home and, moreover, on a very smooth floor. In those days, some "inventors" made a whole sensation with their inventions. So, a German sold a Swedish prince an amazing wagon that moved by itself without the use of any force, allegedly due to a mechanism hidden inside the wagon. But the “mechanism” turned out to be people hidden in a stroller.

Almost all large European countries from the 15th-16th centuries there were their own inventors of scooters. In Russia, Kulibin was not the first to invent it either. But he knew nothing about his predecessor. Little do we know about him.

This predecessor of Kulibin was a peasant of the Nizhny Novgorod province Shamshurenkov, who back in 1752 built a self-propelled wagon, which he called a “self-running carriage”. History has covered the fate of this amazing inventor from the people with a darkness of obscurity, and no one knows where the inventor himself and his “self-running carriage” went.

Starting his invention, Kulibin thought that he was implementing an original and fresh idea.

It must be remembered that Kulibin was both a designer-inventor and a builder, and, therefore, put down on paper only what he did not hope to keep in memory. Therefore, reading his drawings related to the scooter is very difficult. At the same time, the text written in pencil was either erased or became illegible. Extraneous entries were also made on the drawings.

It has been established that Kulibin designed both a four-wheeled and a three-wheeled scooter at the same time. Contemporaries mention only three-wheeled. The principle of the mechanism was apparently reduced to the fact that the rear wheels rotated with the help of a ratchet placed on the axle. Such a device was generally characteristic of the structures of that time. The Obituary, compiled by Kulibin's son, says: "The servant stood on his heels in attached shoes, raised and lowered his legs alternately, without almost any effort, and the one-wheeler rolled rather quickly." Describes the movement of the scooter and Svinyin. The drawings do not give specialists the opportunity to completely unravel the structure of these "shoes" (pedals) and find out their role. It is generally assumed that two rods that were connected to the pedals rotated a vertical axle with a large flywheel on it. When the feet were pressed on the “shoe”, the dogs caught on the teeth, turned the middle gear and set the flywheel in motion. Inertia ensured the uniformity of the course. Braking was achieved by stretching the springs, tending to compress. At high speed braking was impossible, threatening to break the teeth of the drum. Stopping required slower speed. Svinin means braking when he says that "the mechanism of this scooter was so ingeniously arranged that it rolled uphill quickly, and downhill quietly." The device of brakes is of great interest for specialists due to the novelty of ideas and the originality of its implementation. And here the principle of tensioning clock springs, typical for that time, was the basis for braking.

As we have already noted, for mechanics of the 18th century, the device of devices based on the action of clock springs is very characteristic. And Kulibin based braking on this principle, typical for that time. Steering poorly represented by drawings, and one has only to guess about it. Friction reduction was achieved by using a system similar to modern cylindrical bearings. The Kulibino lift, invented to transfer the queen to the upper floors of the palace, had the same bearing arrangement.

On reverse side one drawing relating to a scooter, there is an inscription by Kulibin indicating the method of attaching the wheels to the axle: “The wheels have thick and thin hubs, cut off the ends smoothly, put them on a stick and find, turning, the real center, then outline in all places. At the hubs, it is correct to cut holes for the round and square ends of the axis, make round ones on the round end of the axis, and square tubes of thick copper on the square end, and solder to the wide end of the tube to attach the circle to the hub.

The length of the scooter was supposed to be about 3 meters, the speed of movement was about 30 kilometers per hour. For a scooter, such a speed would be truly enormous, so that our scientists even express serious doubts about the correctness of the Kulibin formula. The Soviet specialist A. I. Rostovtsev, together with the artist, made an axonometric reconstruction of the scooter. Judging by the picture, this is a very beautiful and intricate invention. Some of its details are very curious and original. In fact, in none of the descriptions of scooters that have come down to us from the 18th century, there are no hints of such details as a flywheel, which facilitated the work of a person standing on the heels and eliminated uneven progress, like a gearbox that allows you to change the speed at will and serves at the same time part of the brake; like disc bearings. It is interesting to note that the type of the closest Kulibin wagon was Shamshurenkov's "self-running carriage".

In Europe, where at one time many scooters were invented, only one, owned by Richard (1693), was similar to Kulibin's. Richard's scooter was also set in motion by a lackey standing on the back of the wagon and pressing the pedals. The pedals were connected by means of levers with two ratchet wheels. The wheels were mounted on the rear axle leading the crew. Thus, the pedals, levers, ratchet wheels were homogeneous among these inventors, who did not know each other.

It should be noted that in comparison with European strollers of this type, the Kulibin one was distinguished by the improvement that was mentioned above.

Kulibin, in this fulfillment of his social order, willy-nilly, becomes in line with all other inventors who tried to please the tastes of the ruling class. He could not get out of the shoes of the "court mechanic" and overcome the prejudices of his age. But even then it is noteworthy that he destroyed his invention. Only ten drawings remain, dating from 1784–1786. Whether he felt a reproach to himself in this invention of his, whether he saw in it a fact of his humiliation or an object of frivolous amusements and an object that eats up his time, it is difficult to say. It is significant that he did not even save the drawings in full for his descendants. And he thought about the descendants, and very seriously.

Noteworthy is a very curious fact in the social aspect that immediately after the French Revolution, a democratic type of scooter appeared, the so-called "runners". They were set in motion not by a servant on the heels, but by the rider himself, pushing off the ground with his feet. These runners are considered the forerunners of the modern bicycle.

Article published on 06/21/2014 05:05 PM Last edited on 06/21/2014 05:07 PM Self-running carriage of Kulibin and L. Shamshurenkov(1752, 1791)

Mankind has long dreamed of creating a semblance self-propelled wheelchairs that are able to move without draft animals. This is clearly seen in various epics, legends and fairy tales. May 1752 outside. A festive mood reigned in St. Petersburg, the air was permeated with subtle aromas of spring, the hiding sun sent its last rays. The summer garden was filled with people. Elegant carriages drove along the pavements, and suddenly, among all the carriages, one strange one appears. He walked without horses, quietly and without noise, overtaking other carriages. The people were greatly surprised. Only later it became known that this outlandish invention is “ self-running carriage”, built by the Russian serf of the Nizhny Novgorod province Leonty Shamshurenkov.

Preview - Click to enlarge.

Preview - Click to enlarge.

Also, a year later, Shamshurenkov wrote about what he could do self-propelled sled and a counter up to a thousand miles with a bell ringing every kilometer traveled. Thus, even 150 years before the appearance of the first car with an internal combustion engine, a prototype appeared in serf Rus' modern speedometer and car.

I. P. Kulibin drew up a project in 1784, and in 1791 he built his own “scooter”. In it, for the first time, rolling bearings and a flywheel were used to ensure uniform travel. Using the energy of a rotating flywheel, the ratchet mechanism, driven by pedals, allowed the wheelchair to move freewheeling. The most interesting element of the Kulibin "self-propelled gun" was a gear change mechanism, which is an integral part of the transmission of all cars with internal combustion engines.