Causes of the War of the Spanish Succession

In the first half of the 17th century, the Peace of Westphalia ended the period of religious movements and wars for Western Europe, and the second half of the century saw the desire of the most powerful state in Western Europe, France, to strengthen itself even more at the expense of its weak neighbors and gain hegemony. Given the common life of peoples, to which Europe has already become accustomed, the weak begin to form alliances against the strong in order to restrain its aggressive movements. This is not the first time we have seen this phenomenon: at the beginning of modern history, France also sought to strengthen itself at the expense of its weak neighbors, namely Italy, as a result of which alliances were also formed against it; Even the huge state of Charles V was formed against it, engulfing France from different sides. But neither external obstacles nor internal unrest prevented the growth and strengthening of France, strong in its roundness and unity, and Louis XIV appeared more dangerous than Francis I, especially since there was no powerful Charles V against him. The soul of the alliances against Louis XIV is William of Orange, the leader of a different kind, a representative of a different power than old Charles V. As the Dutch stadtholder and the English king together, William concentrated in himself the representation of maritime trading powers that were not able to fight large continental states with large armies, but they had another powerful means, the nerve wars are money. This remedy has long appeared in Europe as a result of its industrial and commercial development and has become under the power of the sword; a sea power could not field its own large army, but could hire an army and buy an alliance.

Thus, due to the common life of the European peoples, in their activities, in their struggle, a division of occupations is noticeable: some field an army, others pay money, give subsidies - this is, in its way, a combination of labor and capital. Maritime merchant powers are not keen on wars, especially long ones: such wars are expensive; sea powers fight only out of necessity or when trade benefits require it; for them, continental wars are pointless, because they do not seek conquest on the continent of Europe; the goal of their war is trade gain or a rich colony overseas. But now it was necessary for England and Holland to intervene in the continental war. Direct violence, offensive movement, seizure of someone else's property without any pretext were uncommon in the new, Christian Europe, and Louis XIV sought various pretexts to expand his possessions and established the Chambers of Union. But even without violence, conquest and legal tensions, it was possible for European states to strengthen themselves, to annex entire other states, precisely through marriages, inheritances, wills: we know that in this way the Scandinavian states were united at one time, Poland united with Lithuania, and The Habsburgs were especially famous for their ability to arrange profitable marriages and through them to form a vast state through wills and inheritances.

Now we, taught by historical experience and under the influence of the principle of nationality, affirm the fragility of such connections, point out the short duration of the Kalmar Union, the bad consequences of the Jagiellian marriage for Poland, the fragility of the motley monarchy of the Habsburgs; but they did not look that way before, and even now they do not completely refuse to attribute importance to the family ties between the owning houses: the terrible, exterminating war that we recently witnessed began due to the fact that one of the Hohenzollern princes was called to the Spanish throne. When the happy heir of all his relatives, Charles V, formed a vast state from the Austrian, Spanish and Burgundian possessions, no one took up arms against him for this, he was even chosen as the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, because his strength was seen as a bulwark against French power; but now, when the most powerful of the French kings, Louis XIV, turned his attention to the Spanish inheritance, Europe could not remain calm, because there was no equivalent power against the power of the Bourbons. Holland could not be at peace with the thought that between it and the terrible France there would no longer be a possession belonging to a separate independent state; that France, which recently almost destroyed it, will now become even stronger; the Whig party in England, which expelled the Stuarts, could not rest at the thought that the already powerful patron of the Stuarts would also have the forces of Spain; in Vienna they could not come to terms with the idea that Spain would pass from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons, that Austria would cease to be happy with marriages (et tu, felix Austria, nube) and that happiness would pass to France. Austria, Holland and England were supposed to prevent Louis XIV from receiving the Spanish inheritance, and William III was the stadtholder in Holland and king in England.

The fatal Spanish inheritance was supposed to lead to a terrible, general war; but they didn’t want war: the sea powers didn’t want it because of their always-on policy, naturally and necessarily peaceful, because of their natural aversion to spending a penny of labor on a war that would not bring direct trade benefits, immediate profits; The emperor did not want her, according to the custom of non-military Austria, due to lack of funds, due to the bad hope of help from Germany, due to the unfinished, albeit happy, war with Turkey. Louis XIV did not want war either: we saw what a sad state France was in at the end of the 17th century; voices were heard from different sides about the need to stop the warlike policy and could not help but impress the king, no matter how great his pride was, no matter how strong the habit of contemptuously treating opinions that were not similar to his opinions and desires, considering these opinions to be fantasies ; moreover, the last war, which did not end the way Louis would have liked, showed him that it is not very easy to fight coalitions. Everything is thus

The fatal Spanish inheritance was supposed to lead to a terrible, general war; but they didn’t want war: the sea powers didn’t want it because of their always-on policy, naturally and necessarily peaceful, because of their natural aversion to spending a penny of labor on a war that would not bring direct trade benefits, immediate profits; The emperor did not want her, according to the custom of non-military Austria, due to lack of funds, due to the bad hope of help from Germany, due to the unfinished, albeit happy, war with Turkey. Louis XIV did not want war either: we saw what a sad state France was in at the end of the 17th century; voices were heard from different sides about the need to stop the warlike policy and could not help but impress the king, no matter how great his pride was, no matter how strong the habit of contemptuously treating opinions that were not similar to his opinions and desires, considering these opinions to be fantasies ; Moreover, the last war, which did not end the way Louis would have liked, showed him that it is not very easy to fight coalitions. Everyone, therefore, was afraid of war and therefore came up with various means to solve a difficult matter diplomatically.

The Spanish inheritance was opened due to the fact that King Charles II, sickly, undeveloped mentally and physically, ended his miserable existence childless, and with him the Habsburg dynasty in Spain ended. The contenders for the throne were: Louis XIV, son of a Spanish princess and married to a Spanish princess, with whom he had issue; Emperor Leopold I, representative of the Habsburg dynasty, son of a Spanish princess; In his first marriage he had a Spanish princess, the sister of the Queen of France, the daughter of Philip IV, Margaret, to whom her father transferred the inheritance of the Spanish throne in case of the suppression of the male line, while her elder sister, when she married Louis XIV, renounced this inheritance. But Margaret died, leaving Leopold one daughter, Maria Antonia, who married the Elector of Bavaria and died in 1692, leaving a son; this child was the third contender and, on the basis of the will of Philip IV, had more than any other right to the Spanish throne; moreover, this Bavarian prince satisfied the interests of the maritime powers and the political balance of Europe. But Louis XIV did not want to renounce the Spanish inheritance; only to maintain political balance and satisfy the interests of the maritime powers, he offered the following concessions: Spain, passing to the Bourbon dynasty, was to have a king separate from France in the person of one of the grandsons of Louis XIV; to secure Holland, Spain must renounce its Netherlands, which will pass into the possession of the Elector of Bavaria, and Holland will retain the right to have its garrisons in Belgian fortresses, as it has hitherto; maritime powers will receive berths for their ships in the Mediterranean; Dunkirchen will be returned to England to secure its shores from the French landing.

But war was not avoided by this deal: the Elector of Bavaria could be satisfied with the Spanish Netherlands, but the other most powerful contender, Emperor Leopold, did not receive any satisfaction. And so William III, to satisfy the third contender, proposes to divide the Spanish monarchy: the grandson of Louis XIV will take Spain and America, the Elector of Bavaria will take the Netherlands, and the emperor will take the Italian possessions of Spain.

Western historians, who speak so much against the partition of Poland, usually either remain silent about the partition of Spain, or try to show that it was not actually a partition, similar to the partition of Poland; they argue that there was no national connection between the parts of the Spanish monarchy, but the question of national connection is a question of our time; that there was a strong connection between Spain and the Southern Netherlands and, in addition to the national one, proves that they did not separate from Spain when the Northern Netherlands separated from it; there is no doubt that there was much more connection between Spain and its possessions in Italy and the Netherlands than between Western Russia and Poland, between which there was antagonism due to differences in nationality and faith.

Louis XIV did not like William's proposal to give the emperor Spanish possessions in Italy, because a direct increase in the state area was considered much more profitable than placing a relative, albeit a very close one, on the Spanish throne, therefore, Austria received more benefits than France. Louis agreed to cede Spain, the Catholic Netherlands and colonies to the Bavarian prince, so that Naples and Sicily would be ceded to France, and the emperor would take Milan alone. Such an agreement actually followed in the fall of 1698.

When they learned in Spain that they wanted to divide it, King Charles II declared the Prince of Bavaria the heir to all his possessions, but this heir was no longer alive in February 1699, and worries about the fatal inheritance began again. Louis XIV sought to round up France with Lorraine and Savoy, so that the dukes of these lands would receive compensation with Spanish possessions in Italy. At the end of 1699, a second agreement took place: Spain and the Catholic Netherlands were to go to the second son of Emperor Leopold, and France received all Spanish possessions in Italy. However, the emperor constantly avoided entering into these agreements.

But in Madrid they still did not want the division of the monarchy. Of the two candidates now, the grandson of Louis XIV and the son of Emperor Leopold, it was necessary to choose the one who showed more hope that he would keep Spain undivided; the French envoy Harcourt was able to convince the Madrid court that such a candidate was the grandson of Louis XIV, and Charles II signed a will, according to which Spain passed to the second son of the Dauphin, Duke Philip of Anjou; he was to be followed by his brother, the Duke of Berry, followed by Archduke Charles of Austria; if all these princes refuse the inheritance or die childless, then Spain passes to the House of Savoy; In no case should Spain be united under one sovereign with either France or Austria).

Calculation forced Louis XIV to accept this will: although the direct increase of France by certain parts of the Spanish monarchy was more profitable for him, however, having rejected the will of Charles II, in order to carry out the division agreement concluded with William III, Louis had to enter into a war with the emperor, whose son received the entire Spanish monarchy indivisibly and could hope for the strong support of the Spanish people, who rejected the offensive idea of partition; there was little hope for the support of the sea powers, because the vast majority in Holland and especially in England disagreed with William III, considering the elevation to the Spanish throne of one of the grandsons of Louis XIV less dangerous for Europe than the strengthening of France in Italy; all parties in England considered it a wild and incredible thing for England to help France get Italy.

In November 1700, England learned of the will of Charles II. Wilhelm expected that France would at least observe decency and begin negotiations on this matter in connection with last year’s treaty. But France remained deeply silent, and Wilhelm, in great irritation, wrote to a man who completely shared his views, the Dutch rat-pensionary Heinsius, complaining about French shamelessness, that Louis had deceived him; he also complained about the stupidity and blindness of the English, who were very pleased that France preferred a will to a partition treaty. Indeed, in England, where most of all they had in mind trade benefits and most of all spared money for the continental war, loud complaints were heard about the treaty on the division of Spain about the foreign policy of the king, about the terrible losses that Italian and Levantine trade should suffer as a result of the approval French rule in the Two Sicilies. Several times already the Tories had raised a storm in Parliament against the king's ill-intentioned advisers, and the treaty for the division of the Spanish monarchy was the subject of strong parliamentary antics.

Thus, the news that the Spanish monarchy would go entirely to one of the Bourbon princes was received with joy in England; even the ministers directly told the king that they considered this event a mercy from heaven, sent down to deliver him, the king, from the difficulties in which the division agreement had placed him; This agreement is so unpleasant to the people that the king would not be able to carry it out and it would cause him a lot of worries and grief. Numerous pamphlets that appeared on this occasion looked at the matter in exactly the same way, arguing that the power of France would not increase in the least by placing Philip on the Spanish throne; some praised the wisdom of Charles II, others the moderation of Louis XIV. The Whigs did not dare say anything against this. And indeed, it was difficult to say anything other than that it was too early to praise the moderation of Louis XIV, that the placement of Philip on the Spanish throne did not actually strengthen the power of France; but France was already powerful, and the king had not yet figured out the means to increase his possessions, and now, in the event of war with him, the Spanish Netherlands will be at his disposal, and these Netherlands are the key to an independent Netherlands. This is how the warlike Stadtholder party in the Netherlands looked at the matter, in whose brow stood Wilhelm’s personal friend, the Dutch Ratpensionary Anton Heinsius; but the majority of the deputies of the United Provinces looked at the accession of the Duke of Anjou in Spain as the desired outcome of the matter. However, the friends of the English king were not for a separate treaty: they could not help but realize that this treaty was a mistake on William’s part; Heinsius knew what aversion the Spaniards had to the idea of dividing their state, and therefore wanted the undivided transfer of Spanish possessions only not to the Bourbon, but to the Habsburg prince: for this, in his opinion, it was necessary to raise a national movement in Spain in favor of Habsburg and put up 70,000 troops to support the emperor, who was encouraged to immediately enter Italy and conclude an alliance with Denmark, Poland, Venice, Savoy and all other states against France.

But without England it was impossible to start anything, and in England things were going badly for William. Whig ministers struggled with a hostile majority in the lower house and with their Tory comrades who had recently been called into the cabinet. Thus, there was discord in the government. The Tory trend was strengthening in the country. The Tories won the new parliamentary elections because they promised to maintain peace. But Louis XIV was in a hurry to justify the policies of William III and the Whigs. Charles II of Spain died on November 1, 1700; his heir, Philip of Anjou, going to Spain, handed over the management of Belgian affairs to his grandfather, Louis XIV, French troops immediately crossed the Belgian borders and captured Dutch garrisons in the fortresses, and in his justification, Louis announced that he did so to prevent what was directed against him US weapons.

Even before the occupation of Belgium, French troops crossed the Alps and established themselves in Milan and Mantua. The Whigs in England raised their heads, their flying political leaflets called on patriots to arm themselves to protect the Dutch borders, Protestant interests, and the balance of Europe. London merchants were alarmed not by the danger threatening Protestant interests and the balance of Europe, they were alarmed by rumors that Louis XIV intended to ban the import of English and Dutch goods into the Spanish colonies. In this case, the war was already a lesser evil for the peace-loving British. Out of horror, all trade transactions in London stopped for some time. The Tories, in turn, had to calm down. But they had a majority in parliament; in the spring of 1701, a memorial of the Dutch Republic was handed over to parliament, which stated that the States intended to demand guarantees of their future security from Louis XIV, but did not want to start business without the consent and assistance of England; since serious clashes with France may arise from these negotiations, it is advisable for the States to know to what extent they can rely on England. Parliament agreed that the English government should take part in the Dutch negotiations, without, however, giving the king the right to conclude alliances, insisting on maintaining peace.

European Union against Louis XIV

That same month, negotiations began in The Hague. In the first conference, the commissioners of the sea powers demanded the cleansing of Belgium from French troops and, conversely, the right for Holland and England to maintain their garrisons in famous Belgian fortresses; in addition, they demanded for the British and Dutch the same trading privileges in Spain that the French enjoyed. The representative of Louis XIV, Count d'Avo, rejected these demands and began to work on how to quarrel between the English and the Dutch, and began to convince the Dutch representatives that his sovereign could conclude an agreement with their republic and on the most favorable terms, if only England was removed from the negotiations; otherwise, he threatened an agreement between France and Austria and the formation of a large Catholic union. But the Dutch were not deceived: feeling the danger, they stood firmly and unanimously. The Dutch government informed the English about d'Avaux's suggestions, and announced that it would stick firmly to England. “But,” said the States’ letter, “danger is approaching. The Netherlands is surrounded by French troops and fortifications; Now the matter is no longer about recognition of previous treaties, but about their immediate implementation, and therefore we are waiting for British help.”

In the House of Lords, where the Whigs predominated, the States' letter was responded to with an ardent address to the king, authorizing him to conclude a defensive and offensive alliance not only with Holland, but with the emperor and other states. In the House of Commons, where the Tories dominated, they did not share this fervor, they did not want war, fearing that when it was declared, the hated Whigs would again be in control. But there was nothing to be done: the people spoke out loudly in favor of the war, because fears for trade benefits grew more and more intense: news came that societies had been formed in France to seize Spanish trade, and a company had been formed to transport blacks to America. The entire trading class of England cried out about the need for war, curses against deputies appeared in the press, they were accused of forgetting their duties and of treason. The Tories saw that if they continued to oppose the war with France, the parliament would be dissolved and the Whigs would certainly gain the upper hand at new elections. Thus, the lower house was forced to announce that it was ready to fulfill previous agreements, was ready to provide assistance to the allies and promised the king to support European freedom.

But the maritime powers alone could not support European freedom: they needed an alliance of continental European powers, and mainly the strongest of them, Austria. Could Emperor Leopold allow the Spanish monarchy to completely pass from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons, and at a time when Austria was in the most favorable circumstances? Thanks to the Holy Alliance between Austria, Venice, Russia and Poland, Turkey, having suffered severe defeats, had to make important concessions to the allies. According to the Treaty of Karlowitz, Austria acquired Slavonia, Croatia, Transylvania, and almost all of Hungary; but, in addition to these acquisitions, Austria also acquired a guarantee of future success - a good army and a first-class commander, Prince Eugene of Savoy; finally, the triumph of Austria over Turkey, the brilliantly profitable peace, was a sensitive blow for France, because the Porte was its constant ally against Austria, and the Peace of Karlowitz was concluded with the strong assistance of the sea powers, despite France’s efforts to support the war. Everything therefore promised that Austria, having freed its hands in the East, encouraged by brilliant successes here, would immediately turn its arms to the West and take an active part in the struggle for the Spanish inheritance. But Austria accepted this participation very slowly. Her behavior depended, firstly, on her constant slowness in politics, her aversion to decisive measures, and her habit of waiting for favorable circumstances to do everything for her without much strain on her part.

The Austrian ministers, quick to draw up plans and slow when it was necessary to carry them out, were afraid to take up the Spanish question, which contained truly great difficulties. It seemed to them much more profitable to annex part of the Spanish possessions directly to Austria than to fight to exclude the Bourbons from the Spanish inheritance and to deliver it entirely to the second son of Emperor Leopold, Charles; for all the Spanish possessions in Italy, they agreed to cede the rest to the grandson of Louis XIV, even the Catholic Netherlands, which was so contrary to the benefits of the sea powers, and Louis XIV also did not consider it beneficial for himself to cede all Spanish possessions in Italy to Austria.

In Vienna they really wanted to acquire something, not to give the entire Spanish monarchy to the Bourbons, and at the same time they could not come to any decision, waiting, out of habit, for favorable circumstances. Secondly, the behavior of Austria depended on the character of Emperor Leopold, a man of little talent, slow by nature, suspicious and highly dependent on his confessor; slowness was best expressed in his speech, fragmentary, incoherent; the most important matters lay on the emperor’s table for weeks and months without a decision, and in the present case the emperor’s determination was also influenced by the Jesuits, who really did not like the alliance of Austria with the heretics - the British and the Dutch; the Jesuits, on the contrary, worked to bring together the Catholic powers of Austria, France and Spain, so that with their combined forces they could restore the Stuarts in England.

At the Viennese court, however, there was a party that demanded decisive action, that demanded war: it was the party of the heir to the throne, Archduke Joseph, and Prince Eugene of Savoy; but the emperor’s old advisers acted against her, fearing that with the outbreak of war all importance would pass from them to Joseph’s warlike party. In such hesitation and waiting, the Viennese court was disturbed by the news that Charles II had died, that the new king, Philip V, was received with triumph in Madrid, that he was recognized with the same joy in Italy, that French troops had already entered this country and occupied Lombardy, that the conferences in The Hague could end in a deal between France and the sea powers, and Austria would get nothing. Things were moving in Vienna. In May 1701, the Austrian envoy in London proposed to King William that the emperor would be pleased if Naples, Sicily, Milan and the Southern Netherlands were ceded to him. The last requirement completely coincided with the interests of the maritime powers, who needed the possession of a strong power between France and Holland. In August, the naval powers made a final proposal to the Viennese court, which consisted of the following: a defensive and offensive alliance against France; if Louis XIV denies Austria a land reward and the maritime powers certain guarantees of their safety and benefits, then the allies will use every effort to take possession of Milan, Naples, Sicily, Tuscan coastal areas and the Catholic Netherlands for the emperor; England and Holland provide for themselves the conquest of the transatlantic Spanish colonies. On this basis, the next month the European Union was concluded between the emperor, England and Holland: Austria fielded 90,000 troops, Holland - 102,000, England - 40,000; Holland - 60 ships, England - 100.

At the very time when the great alliance was being sealed in The Hague, Louis XIV, with his orders, seemed to want to speed up the war; he dealt the British two sensitive blows: the first was dealt to their material interests by prohibiting the import of English goods into France; Another blow was dealt to their national feeling by the proclamation, after the death of James II, of his son as King of England under the name of James III, while shortly before that act of parliament the Protestant inheritance was approved: after the death of the widowed and childless King William III, his sister-in-law, the youngest daughter of James, entered the throne II Anna, the wife of Prince George of Denmark, after her the throne passed to the Elector of Hanover, the granddaughter of James I Stuart from his daughter Elizabeth, the wife of the Elector Frederick of the Palatinate (the ephemeral king of Bohemia).

As a consequence of these insults from France, William III received from his subjects many addresses of devotion; the country loudly demanded an immediate declaration of war on France and the dissolution of the non-belligerent parliament. During the new elections, the Tory candidates managed to hold out only because they shouted louder against Louis XIV than their rivals, the Whigs, and demanded war louder. In January 1702, the king opened the new parliament with a speech in which he reminded the lords and commons that at the moment the eyes of all Europe were turned to them; the world awaits their decision; we are talking about the greatest public goods - freedom and religion; a precious moment had arrived for the maintenance of English honor and English influence in the affairs of Europe.

This was William of Orange's last speech. He had not enjoyed good health for a long time; in England they were used to seeing him suffering, surrounded by doctors; but we were also accustomed to seeing that, as circumstances required, he did his best and quickly got down to business. At the time described, he hurt himself by falling from a horse, and this apparently slight bruise brought William closer to the grave. The king told those close to him that he felt his strength diminishing daily, that he could no longer be counted on, that he was leaving life without regret, although at present it offered him more consolation than ever before. On March 19, Wilhelm died. His sister-in-law Anna was proclaimed queen.

Modern historians glorify William III as the man who finally established the freedom of England in political and religious terms and at the same time worked hard to liberate Europe from French hegemony, linking the interests of England with the interests of the continent. But contemporaries in England did not look at things that way. Against their will, forced by necessity, they decided on the revolutionary movement of 1688 and looked with dissatisfied eyes at its consequences, when they had to place a foreigner on their throne who did not belong to the dominant Episcopal Church. They looked at the Dutch stadtholder with suspicion, they were afraid of his lust for power, they were also afraid that he would involve the country in continental wars and would spend English money for the benefit of his Holland; hence the parliament’s distrust of the king, the opposition to his intentions on the part of both parties - both the Tories and the Whigs, and the stinginess in providing subsidies for the war. Wilhelm, constantly irritated by this distrust and obstacles to his plans, could not treat his subjects kindly, and was not distinguished by kindness by nature: hidden, silent, indiscreet, constantly surrounded only by his Dutch favorites, with them he thought about the most important English affairs, Wilhelm could not possibly be popular in England. The more willingly the popular majority saw Queen Anne on the throne.

The new queen was not distinguished by any visible merits: her upbringing was neglected in her youth, and in her mature years she did nothing to make up for this deficiency; spiritual lethargy expressed itself in indecision and inability to work hard; As soon as the question emerged from the series of daily phenomena, she already became confused. But the more she needed someone else’s advice, the less independent she was, the more she wanted to appear so, because she considered independence necessary in her royal position, and woe to the unwary who would too clearly want to impose his opinion on the queen. Ardently committed to the Anglican Church, Anna treated both papism and the Protestant heresy with equal disgust, which is why she seemed to our Peter the Great “the true daughter of the Orthodox Church,” in his own words. Anna's shortcomings could not be sharply expressed before her accession to the throne: her good qualities were visible, her impeccable married life; but, of course, her most precious quality was the one that William lacked: she was English and distinguished by her commitment to the Anglican Church.

As for political parties, Anne's accession to the throne was greeted by the Tories with joyful hopes, and by the Whigs with distrust. The Whigs suspected Anna of being attached to her father and brother; the Whigs acted hostilely against Anne under William and were the culprits of a strong quarrel between them; The Whigs raised the question: Shouldn't the throne, after William's death, go directly to the Hanoverian line? The Tories stood all the more zealously for Anna. Since the conviction was rooted that the son of James II, proclaimed king on the continent under the name of James III, was a fake, the strict zealots of the correct succession to the throne considered Anna the legitimate heir to the throne immediately after the death of James II, and looked at William only as a temporary ruler. Anne's attachment to the Anglican Church made her an idol for all adherents of the latter, offended by the fact that King William was not one of them, and was a heretic in their eyes. Both universities, Oxford and Cambridge, always distinguished by their zeal for the Anglican Church, greeted Anna with fiery addresses; Oxford theologians proclaimed that now only with the accession to the throne of Anne, the Church was secured from the invasion of heresy, now a new, happy era had come for England.

In addition to the Whigs and Tories, there was a Jacobite party in England, which saw the legitimate king in the young James III, and this party was not hostile to Anna, because James III was still very young and could not immediately come to England to regain his father’s crown, and the leaders of his party thought it most prudent to wait; The disturbed health of the thirty-seven-year-old queen did not promise a long reign, and they knew that Anna could not stand her Hanoverian relatives, and even more so they could count on her affection for her brother. But the more hopeful the Jacobites were, the more fearful the adherents of the revolution of 1688 were; They were especially afraid of the influence of the Earl of Rochester, the queen’s uncle on her mother’s side, the son of the famous Lord Clarendon: Rochester was a famous Jacobite, and they were afraid that he would raise people like himself to the top, who would change foreign policy, tear England away from the great alliance and bring them closer to France.

John Churchill, Earl of Marlborough

But the fear was in vain: the new queen immediately let the Dutch government know that she would strictly adhere to the foreign policy of her predecessor; the same was announced in Vienna to other friendly powers. The party, conscious of the need to take an active part in the war against France, was, for reasons known to us, as strong in the first days of Anne as in the last days of William; and although interference in continental affairs, war for local interests, spending money on a war that did not promise immediate benefits could never be popular on the island, and the peace party should have prevailed at the first favorable opportunity and unleashed a war, however, such a favorable circumstance now it hasn't happened yet. As for the queen, the representative of the war party, Lord John Churchill, Earl of Marlborough, had the strongest influence on her at the time described.

The Earl of Marlborough himself had a strong influence on the queen, but even more powerful was his wife, who had a close friendship with Anna when both were not yet married. The friends had opposite characters, because the Countess of Marlborough (nee Sarah Jennings) was distinguished by extreme energy, expressed in all her movements, in her gaze, in strong and fast speech, she was witty and often evil. It is not surprising that the princess, who was lazy in mind, became strongly attached to the woman, who relieved her of the duty of thinking and speaking and so pleasantly entertained her with her mobility and her speech. Anna Stewart married the insignificant George of Denmark, and Sarah Jennings married the most prominent of the Duke of York's courtiers, Colonel John Churchill. It was difficult to find a more handsome man than John Churchill. He did not receive a school education and had to acquire the necessary information himself; but a clear mind, extraordinary memory and the ability to deal with the most remarkable people, whom he constantly met due to his position, helped him in the matter of self-education: extreme accuracy and perseverance in every matter early pushed him out of the crowd and showed him as a future famous figure; but while moving out of the crowd, the clever, ambitious man knew how not to push anyone, did not prick his eyes with his superiority, and lived in great friendship with the mighty of the earth. But cold, calculating, cautious and clever with everyone else, Churchill completely lost control of his wife, to whose influence he constantly submitted and to the detriment of his glory.

Churchill began his military activities in the Dutch wars of the seventies under the eyes of French commanders. James II raised him to the rank of lord, and in 1685 Lord Churchill performed an important service for the king by taming the Monmouth rebellion; but when Jacob began to act against the Anglican Church, Churchill, a zealous supporter of this Church, lagged behind him, and his transition to the side of William of Orange determined the quick and bloodless outcome of the revolution. Churchill was elevated to Earl of Marlborough for this, but soon did not get along with William, especially when his wife was insulted by Queen Mary, and a rift ensued between the royal court and Princess Anne. The dissatisfied Marlborough entered into relations with his old benefactor, James II, and even reported details about the English enterprise against Brest. However, later he again became close to William and was privy to all the king’s plans regarding foreign policy. William entrusted him with command of the auxiliary English army in the Netherlands and the final consolidation of continental alliances; the king saw in him a man who united the warmest heart with the coldest head.

It is easy to understand that Marlborough did not lose anything with the death of William and the accession to the throne of Anne, who looked at him as the most devoted person to herself. Lord Marlborough immediately received the highest order (of the Garter) and command of all English troops, and his wife was given the position of first lady of state. Marlborough, in fact, did not belong to any party, and yet both parties had reason and benefit to consider him one of their own: the Tories counted on his attachment to the Anglican Church, on his connections, on the persecution that he suffered during the reign of the Whigs under William, and hoped to have him on their side on all questions of domestic policy; the Whigs, for their part, saw that Lady Marlborough was in close contact with all the heads of their party, that the notorious Whig, Lord Spencer, was Marlborough's son-in-law; finally, the Whigs were in favor of the war, why their interest merged with the interests of the commander-in-chief of all the English troops, and the Whigs told him that, although they did not hope to occupy government seats in the present reign, they would nevertheless contribute to everything that would be done for the good of the nation .

Marlborough's first order of business was to go to Holland to cement the alliance between the two sea powers, which had necessarily weakened after the death of the king and stadtholder. The presence in Holland of the most influential person in the English government was also necessary because Louis XIV tried to tear Holland away from the great union with promises to cleanse Belgium and make other concessions, as a result of which some deputies in the United States began to lean toward peace with France. Marlborough solemnly, in the presence of foreign ambassadors, announced that the Queen would religiously fulfill the treaty of alliance, as a result of which the States finally rejected the French proposal. Meanwhile, in England, Rochester, taking advantage of Marlborough's absence, hurried to give the final triumph to the Tory party and managed to form a ministry from its members; we saw Marlborough's attitude towards the Tories, and he hastened to assure the States that the change in the English ministry would not have any influence on the course of foreign affairs. But Lady Marlborough took a strong part in the fight against the queen's uncle, who became a Whig. Here the friends collided for the first time: Queen Anne noticed a sharp difference between the respectful language of all the others who addressed her on this matter, and the unceremonious, demanding language in which Lady Sarah, out of old habit, spoke to her: from then on, a cooling began between the friends.

But be that as it may, the same conviction in the need for war with France to protect English interests prevailed in society, as in the latter part of William’s reign, and therefore changes in the ministry could not stop things. The national view was expressed in the State Council convened to finalize the question of war; voices were heard: “Why such an expensive and difficult intervention in continental unrest? Let the English fleet be in good condition; as the first fleet in Europe, let it guard the shores and protect trade. Let the continental states torment each other in a bloody struggle; the trade and wealth of central England will all the more increase. Since England does not need continental conquests, she should help her allies only with money, and if she absolutely must fight, she should limit herself to a naval war; in order to fulfill allied obligations with Holland, it is necessary to enter the war in the sense of only a helping power, but not independently.” All these opinions, as expressions of the fundamental national view, were very important for the future, for they were bound to prevail at the first opportunity; but now this convenience was not available to them when the majority was convinced of the need to restrain the terrible power of France, and war was declared.

Beginning of the War of the Spanish Succession

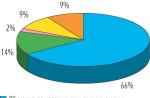

At the beginning of this war, precisely in the summer of 1702, the political and military advantage was not at all on the side of the allies, despite the great name of the European Union. The Northern powers refused to participate in the war against France; in the eastern regions of the Austrian monarchy an uprising was ready to break out; in Germany, Bavaria and Cologne were on the side of France, covered by Belgium, the Rhine Line, neutral Switzerland and possessing the forces of Spain, Portugal, and Italy. The Allies were supposed to field 232,000 troops, but in reality they could have had much less, so that the forces of Louis XIV and his allies were superior by 30,000 people. The income of France (187,552,200 livres) was equal to the sum of the income of the emperor, England and Holland; in addition, in his orders, Louis was not constrained by any parliament, any provincial ranks, or any individual nationalities; finally, the possessions of the continental allies were opened, while France was protected by strong fortresses.

Indeed, the first two years of the war (1702 and 1703) could not promise a favorable outcome for the European Union, despite the fact that on the part of France there were clear signs of decrepitude - a consequence of the materially and morally unproductive system of Louis XIV. An ally of France, Elector of Bavaria Max Emmanuel took the important imperial city of Ulm; in Italy, the emperor's commander, Prince Eugene of Savoy, could not cope with the French, who were under the command of Vendôme, and had to lift the siege of Mantua. Austria, due to shortcomings in internal governance, could not wage war with sufficient energy. “It is incomprehensible,” wrote the Dutch envoy, “how in such a vast state, consisting of so many fruitful provinces, they cannot find means to prevent state bankruptcy.” Income fluctuated because certain areas provided more or less; sometimes individual regions received the right not to pay anything for a year or more. The annual income extended to 14 million guilders: of this amount no more than four million came to the treasury; The national debt extended to 22 million guilders. The long Turkish war contributed greatly to the financial breakdown. The government did not dare to impose emergency taxes for fear of driving the peasants, who were already in a miserable situation, to despair, and therefore preferred to borrow money with payments ranging from 20 to 100 percent. But such financial distress did not prevent Emperor Leopold from incurring large expenses when it came to court pleasures or when his religious feelings were affected.

The treasury was eaten up by a huge number of officials who received their salaries, and during campaigns, salaries were delivered to the troops either very late or not at all, so that the commanders at the end of the campaign, and sometimes even in the middle of the campaign, were forced to leave the army and go to Vienna in order to speed up the sending of money . Constant hatred reigned between the commanders and officials of the court military council (Gofkriegsrat); especially all the generals looked at the president of the Khofkriegsrat as their mortal enemy; The emperor's eldest son, the Roman King Joseph, pointed to the managers of military and financial affairs in Vienna as the perpetrators of all evil. The Imperial Generalissimo learned about political negotiations and military events only from the Viennese newspaper. Production in the army was not at all based on ability, and the foreign ambassadors at the Viennese court were most amazed at the cynical frankness with which each officer spoke about the inability and dishonesty of his comrades and generals.

There was also a reformation party at the Viennese court: it consisted of Prince Eugene, Prince Salm, the counts of Kaunitz and Bratislava, and was led by the Roman King Joseph; but all her aspirations were dashed by the emperor’s irresistible distrust of new people and new thoughts. The Dutch envoy responded that he would rather drink the sea than act successfully against the crowd of Jesuits, women and Leopold's ministers. This disorder of the government machine in Austria was also accompanied by unrest in Hungary and Transylvania, where peasants burdened with taxes rose up, and these uprisings could intensify, because the eastern part of the state was exposed to troops as a result of the war in the west. At first, the Hungarian unrest was not of a political nature, but things changed when the rebels came into contact with Franz Rakoczy, who lived in exile in Poland. Prudent people demanded that the Hungarian unrest be stopped as soon as possible, either by mercy or severity; but the emperor preferred half measures - and the fire flared up, and at the same time the predicament of Austria in the European war reached its highest point: the army did not receive recruits, the soldiers were hungry and cold. This situation was supposed to lead to changes in Vienna: the presidents of the military and financial councils lost their places, finances were entrusted to Count Staremberg, and military administration was entrusted to Prince Eugene.

Thus, in the first period of the war, Austria, due to the state of its management, could not energetically contribute to the successes of the Allies. The naval powers, England and Holland, also could not wage a successful war in the Spanish Netherlands. Here the two campaigns of 1702 and 1703 ended unsatisfactorily. Marlborough, who commanded the allied forces, was in despair and rightly blamed the failure on the Republic of the United States, which hindered him with merchant frugality regarding people and money; In addition, the parties fighting in the united provinces, the Orange and the Republican, tore the army apart, the generals quarreled and refused to obey each other. The commander was embarrassed by the so-called “camping deputies” who were with him with a control role: they were in charge of food supplies for the troops, appointed commandants to the conquered places, had a voice in military councils with the right to stop their decisions, and these deputies were not military people at all. Finally, in Holland there was expressed distrust of the foreign commander; Pamphlets against Marlborough and his bold plans appeared in the press. Meanwhile, in England, as a result of the unsatisfactory nature of the two campaigns, people who were against the continental war raised their heads.

Portrait of Philip V of Spain, 1701

Great successes for England and Holland could be expected from maritime enterprises against Spain. We have seen the reasons why Spain fell asleep towards the end of the 17th century. The events that followed at the beginning of the 18th century were supposed to awaken her: indeed, the people were agitated when they heard that the hated heretics, the English and the Dutch, were planning to divide the Spanish possessions, and therefore the accession to the throne of Philip V with the guarantee of indivisibility found strong sympathy in Spain. Unfortunately, the new king was not able to take advantage of this sympathy. The Spanish infanta, whom Mazarin married Louis XIV, seemed to bring a sad dowry to the Bourbon dynasty: the offspring resulting from this marriage revealed features of the decrepitude that distinguished the last Habsburgs in Spain. Philip V appeared on the Spanish throne as such a decrepit youth, for whom the crown was a burden and any serious activity was a punishment; He accepted his grandfather’s smart, eloquent instructions and letters with indifferent submission, entrusting others with the responsibility of answering them and conducting all correspondence, even the most secret. Philip did the same in all other matters.

It was clear that a king with such a character needed a first minister, and Philip V found himself a first minister in a sixty-five-year-old old woman who, in contrast to the young king, was distinguished by youthful liveliness and masculine willpower: she was Maria Anna, by her second marriage the Italian Duchess of Bracciano-Orsini , daughter of the French Duke of Noirmoutier. In Italy, she maintained contact with her former fatherland and was an agent of Louis XIV in Rome, was very involved in the transfer of the Spanish inheritance to the Bourbon dynasty during the marriage between Philip V and the daughter of the Duke of Savoy, and when the bride went to Spain, she went with her and Princess Orsini as the future Chief Chamberlain. Many people wanted to master the will of the young king and queen; but Orsini defeated all rivals and brought Philip V and his wife into complete dependence on herself. From the party at the Madrid court, Orsini chose the most useful for the country - the National Reformation Party - and became its leader.

Louis XIV wanted, through Orsini, to rule Spain as a vassal kingdom; but Orsini did not want to be an instrument in the hands of the French king, and even if she was guided by the impulses of her own lust for power, only her behavior and desires, so that the influence of a foreign sovereign would not be noticeable in the actions of the Spanish king, coincided with the good and dignity of the country and contributed to the establishment of the Bourbon dynasty on the Spanish throne. But it is clear that with such a desire to make himself and the government in general popular, Orsini had to face the French ambassadors who wanted to dominate in Madrid.

Under such and such conditions, Spain had to participate in the war that Western Europe was waging because of it. In 1702, the British's intention to capture Cadiz failed, but they managed to capture the Spanish fleet, which was coming from the American colonies with precious metals. Spain should have expected a most dangerous struggle when Portugal joined the European Union, and Vienna decided to send Archduke Charles, the second son of Emperor Leopold, to the Iberian Peninsula as a contender for the Spanish throne; They hoped that in Spain there were many adherents of the Habsburg dynasty, many dissatisfied people who wanted change in general, and that under these conditions Philip V could easily be replaced by Charles III. This Charles was the favorite son of Emperor Leopold, because he looked like his father, while the eldest, Joseph, due to the dissimilarity of character and aspirations, stood at a distance from his father and even in opposition. Well-intentioned, conscientious, but sluggish, undeveloped, eighteen-year-old Charles had to set off on a distant enterprise - to conquer the Spanish throne, surrounded by parties, among which only some cardinal or court lady, grayed in intrigue, could make his way. After much preparation and obstacles, only in March 1704 the Anglo-Dutch fleet brought to the mouth of the Tagus “the Catholic king not by God, but by heretical mercy,” as stated in Jacobin pamphlets in England.

When going ashore, Charles receives news that his bride, the Portuguese princess, died of smallpox, and her father, Don Pedro, fell into deep melancholy. In Portugal, nothing was ready for war, the army did not receive pay, did not know how to wield weapons, did not want to fight; all the horses that were of any use were recently exported either to Spain or France; the people did not want war and looked with hatred at the heretical foreign regiments. Be that as it may, Portugal was firmly tied into an alliance by a trade agreement with England, according to which Portuguese wines were to be sold in Britain, where they were charged a third less duty than French wines, for which Portugal undertook not to allow any woolen goods to enter its territory, except English.

In addition to Portugal, the union acquired another member - the Duke of Savoy-Piedmont. Holding in their hands the keys to Italy and France and being between the possessions of two powerful dynasties, the Bourbon and Habsburg, the Dukes of Savoy and Piedmont had long been forced to strain all their attention to maintain independence in the struggle of their strongest neighbors and to strengthen themselves at every opportunity, taking advantage of this struggle ; Therefore, they were distinguished by their frugality, for they always had to maintain a significant army, and they were also distinguished by the most unceremonious policy: being in an alliance with one of the warring parties, they always conducted secret negotiations with the one against which they had to fight. During the full power of Louis XIV, Piedmont had a bad time: it was almost a vassal land of France. But when Louis’ lust for power began to provoke coalitions, when William of Orange became king of England and Austria, which was heavy on the rise, began to move, Piedmont’s position became easier: Louis XIV began to ingratiate himself with its Duke Victor Amedee II and, in order to tie the latter to himself, married two of his grandchildren to two his daughters. Victor Amedeus, as the father-in-law of Philip V of Spain, naturally had to be in alliance with him and with his grandfather; Moreover, with the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession, Louis XIV transferred the main command over the combined Franco-Spanish-Piedmontese troops to the matchmaker. But this was just an empty title: the French commanders, knowing the Piedmontese policy, looked at the orders of Victor Amedee with extreme suspicion and did not at all consider themselves obliged to obey him; The French envoy in Turin also treated him the same way. The arrogant treatment of his son-in-law, the King of Spain, in a decent meeting with him should have further increased the irritation of Victor Amedee. The Duke's complaints to Louis remained without consequences in practice: the king heard cries from everywhere about the treachery of his matchmaker, about the need to get rid of his unfaithful ally without ceremony.

Already in May 1702, the Dutch envoy informed from Vienna that the imperial ministers had established relations with the Duke of Savoy and at the same time Victor Amedee made a request in London whether the English government would help him in obtaining Milan. Negotiations dragged on for a whole year: Victor Amedey kept bargaining, kept bargaining for more land for himself and brought despair to the allies, who called for the vengeance of heaven and the contempt of humanity against the shameless, suspicious and greedy Savoyard, and Victor Amedey kept asking for more land, when suddenly, finally, in September 1703 years, he was disturbed in his trade by the news that the French were convinced of his treason. Vendôme captured many Piedmontese generals, disarmed some cavalry regiments and demanded the surrender of two fortresses as a guarantee for the duke's loyalty. Then Victor Amedee directly declared himself against France and moved to the Great Alliance, taking what was given, that is, the Milan and Mantua regions, with prospects for large rewards in the event of a successful end to the war.

Battle of Blenheim

Decisive success on the side of the alliance was revealed in 1704, when Marlborough decided to unite with Prince Eugene in Bavaria. The consequence of this connection was on August 13 the brilliant victory of the allies over the Franco-Bavarian army, which was under the command of the Elector of Bavaria and the French generals Tagliard and Marcin: this victory bears a double name: for the village of Blenheim or Blindheim, where the British won, and for the town of Hochstedt, where they won Germans; the allies paid for the victory with 4,500 killed and 7,500 wounded. The French and Bavarians, out of 60,000 troops, barely saved 20,000; Marshal Tagliard and up to 11,000 troops were captured. Here the character of the French was clearly revealed: fervent in the offensive, they are impatient, soon lose their spirit in case of failure and allow themselves to be captured by entire regiments. As a result, the Blindheim defeat had dire consequences for the French: despite heavy losses, they could still hold out in Bavaria, and Elector Max suggested this; but the French with their general Marcin completely lost their spirit; flight seemed to them the only means of salvation, and the fugitives stopped only on the left bank of the Rhine; Thus, as a result of one defeat, the French cleared Germany, one defeat crushed the glory of the French army, which they used to consider invincible; This surrender in large crowds on the battlefield made a particularly strong impression, and as much as the French fell in spirit, so did their enemies rise.

The winners wanted to erect a monument in honor of Blindheim’s victory and write on it: “May Louis XIV finally know that no one should be called happy or great before death.” But Louis at least bore his misfortune with dignity; In all his correspondence, the most secret, he knew how to maintain clarity and firmness of spirit, and never stooped to useless complaints, having one thing in mind - how to get things right as quickly as possible. He expressed only regret for Marshal Tagliard, sympathy for his grief and the loss of his son, who died in a disastrous battle; The king showed even more regret for his unfortunate ally, the Elector of Bavaria, he wrote to Marcin: “The present position of the Elector of Bavaria worries me more than my own fate; if he could conclude an agreement with the emperor that would protect his family from captivity and the country from devastation, then this would not upset me at all; assure him that my feelings for him will not change because of this and I will never make peace without taking care of returning all his possessions to him.” Elector Max paid Louis in the same coin: when Marlborough persuaded Prince Eugene to offer him the return of all his possessions and a significant amount of money annually if he turned his arms against France, the Elector did not agree.

The campaign, which concluded with such a brilliant victory, cost Marlborough dearly: his health suffered greatly from the terrible stress. “I am sure,” he wrote to his friends, “that when we meet, you will find me aged ten years.” The news of Blindheim's victory was received with delight in England both in the palace and in the crowds; In the midst of this delight, comments from the hostile party were also heard. Before the victory, people who were against the continental war loudly condemned Marlborough's movement into Germany, shouted that Marlborough had exceeded his power, abandoned Holland without protection and was exposing the English army to danger in a distant and dangerous enterprise. The victory did not silence the critics: “We won, no doubt, but this victory is bloody and useless: it will exhaust England, but will not harm France; A lot of people were taken from the French and beaten, but for the French king it’s the same as taking a bucket of water from the river.” Marlborough responded to this last comparison: “If these gentlemen allow us to take one or two more buckets of water like this, then the river will flow calmly and will not threaten our neighbors with flooding.”

Particularly hostile to Marlborough was that part of the Tory party that was called the Jacobites, that is, adherents of the pretender, James III Stuart. It is understandable that these Jacobites must have looked unfavorably on a victory that humiliated France, for only with the help of France could they hope for the return of their king, James III. Annoyed by the glory of Blindheim's winner, the Tories tried to oppose him to Admiral Rook, whose exploits in Spain were more than doubtful; one thing could be put forward in his favor - this was assistance in the capture of Gibraltar. The capture was made easier by the fact that the Spanish garrison consisted of less than 100 people. The British did not take Gibraltar from Philip V in favor of Charles III: they took it for themselves and retained this key to the Mediterranean Sea forever.

Relations with the English parties could only make Marlborough work harder for the continuation, and successful continuation of the war. The weakest point of the alliance was Italy, where Victor Amedee could not resist the best French general, the Duke of Vendôme, where Turin was ready to surrender. It was impossible to separate part of the army that was under the command of Marlborough and Prince Eugene to Italy without harming military operations in Germany; a new army could not be demanded from the emperor, because the Austrian troops were engaged against the Hungarian rebels. Marlborough looked everywhere to get troops, and settled on Brandenburg, which Elector Frederick accepted the title of King of Prussia. Marlborough himself went to Berlin: here they were very flattered by the courtesy of the famous Blindheim winner and gave him 8,000 troops for English money.

Camisards

In Hungary, things were going well for the emperor: the rebels who had initially threatened Vienna suffered a severe defeat, but Rakoczi still held out. Marlborough really wanted to end this war harmful to the union, and he insisted that the emperor give his Hungarian subjects complete religious freedom; but the emperor, under the influence of the Jesuits, did not want to agree to this; The Jesuits saw that they had the right to fear an alliance with heretics. But Louis XIV, who fanned the Hungarian uprising, saw a similar phenomenon in his own possessions, where the Protestant population rebelled in the Ceven mountains. As a result of persecution, religious enthusiasm reached its highest degree here: prophets appeared, children prophesied; the government intensified the persecution, but those persecuted took advantage of the war, the withdrawal of garrisons from the cities of Languedoc, rebelled, and began a guerrilla war; the leaders of the troops were prophets (voyants); the most important place was given to the one who was distinguished by a greater degree of inspiration; one of the main leaders was a seventeen-year-old boy, Cavalier; the most important leader was a young man, 27 years old, Roland, who combined with wild courage something romantic that amazed the imagination. Roland soon had 3,000 troops who called themselves children of God, and Catholics called them camisards (shirt makers) because of the white shirts they wore at night to recognize each other. (This is how they usually explain it, but it is known that sectarians, distinguished by a similar mood of spirit, love to use white shirts in their meetings.) The caves in the mountains served them as fortresses and arsenals; They destroyed all the churches and priestly houses in the Seven Mountains, killed or drove out the priests, captured castles and cities, destroyed the troops sent against them, collected taxes and tithes.

Languedoc officials gathered and decided to convene the police. When Paris learned about these events, Chamillard and Maintenon first conspired to hide them from the king; but it was impossible to hide it for long when the uprising spread, when the Governor-General of Languedoc, Count Broglie, was defeated by the Camisards. The king sent Marshal Montrevel with 10,000 troops against the rebels; Montrevel defeated Roland and wanted to first put out the rebellion by gentle means; but when the Camisards shot those of their own who accepted the amnesty, Montrevel began to rage. The Catholic peasants also armed themselves against the Camisards under the command of a hermit. This holy militia, as the pope put it, began to commit robbery against friends and foes so much that Montrevel had to pacify it; the camisards did not subside; Miracles happened between them: one prophet, to maintain his faith, climbed onto a blazing fire and came down from it unharmed. But the year 1704 was unhappy for the Camisards: Cavalier was forced to enter into an agreement with the government and left France; Roland was defeated and killed; after the Battle of Blindheim, the vast conspiracy of the Camisards failed; their remaining leaders were burned, hanged, and the uprising died down, especially since the government, busy with a terrible external war, turned a blind eye to Protestant religious gatherings.

War of the Spanish Succession 1705–1709

The war with the Camisards ended very conveniently in 1704, because by the next year Louis XIV needed to think about a defensive war! The first days of 1705 in London there was a celebration on the occasion of the arrival of Marlborough with trophies and noble captives. The House of Commons presented an address to the Queen with a request to perpetuate the glory of the great services rendered by the Duke of Marlborough. The Duke received the royal estate of Woodstock, where they built a castle and named it Blenheim. The Emperor gave Marlborough the title of prince and also an estate in Swabia. Only Oxford University, which belonged to the Tory party, insulted Marlborough by placing him in its solemn speeches and poems completely on an equal footing with Admiral Rooke.

Marlborough, back in 1704, came to an agreement with Prince Eugene about the campaign of 1705, persuaded to attack France from the Moselle, where it was less fortified; In early spring, both armies were supposed to begin the siege of Saarlouis, and they were supposed to enter into relations with the Duke of Lorraine, who was only unwillingly for France. Louis XIV also did not waste time, prepared and in the spring of 1705 he could write: “The enemy does not have as much infantry as I have in the Flanders, Mosel and Rhine armies, although in cavalry he is almost equal to me.” But Louis XIV's main advantage was that he could dispose of his relatively numerous troops as he wished, while Marlborough spent his time in The Hague in the spring of 1705 persuading the Dutch government to agree to his plan. When he finally forced this agreement and appeared with an army on the Moselle, he found in front of him a large, sufficiently equipped French army under the leadership of the good General Marshal Villars, while he himself did not have the famous comrade of the Battle of Blindheim: the emperor transferred Prince Eugene to Italy to improve affairs there, and instead of Eugene Marlborough had to deal with Margrave Louis of Baden, who did not move, making excuses either by illness or by insufficient supplies for his troops.

The news of the death of Emperor Leopold (May 5, New Year) gave the English commander hope that under his energetic successor, Joseph I, things would go faster. As we have seen, Joseph promised to be an energetic sovereign when he was the heir, when he was the head of the militant party, the head of the opposition to his father’s ministry, his father’s system. And indeed, at first there was something similar to energetic action in Vienna; but soon afterwards everything went as before, as a result of which neither Marlborough on the Moselle nor Eugene in Italy could do anything during the entire year 1705; only in Spain were the allies happier: Barcelona surrendered to Archduke Charles; in Catalonia, Valence, Arragonia he was recognized as king. In 1706, things also went well in Spain for the allies: Philip V had to leave Madrid. On the other hand, things went poorly for the French in the north from the Netherlands: here in May Marlborough defeated the Elector of Bavaria and Marshal Villeroy at Romilly, near Leuvain, as a result of which the French were driven out of Belgium; finally they were driven out of Italy; and although at the end of the year affairs in Spain took a favorable turn for France, thanks to a popular uprising in favor of Philip V out of hatred of the heretics who supported Charles III, this success could not compensate for the losses in Italy and Belgium, and Louis XIV began to think how would end the unhappy war at the expense of the people who so diligently defended the throne of his grandson: he proposed the division of Spanish possessions, Spain and America ceded to Charles III, Belgium to Holland, holding only Italian possessions for Philip V. But the Allies rejected the proposal.

The campaign of 1707 began with a brilliant victory of the Franco-Spanish troops over the allies (English, Dutch and Portuguese), won at Almanza by the Duke of Berwick (the illegitimate son of James II Stuart). On the German side, the French also made a successful offensive movement and penetrated as far as the Danube; but the Austrian troops captured Naples, and on the other hand penetrated into Provence, although they were soon to leave it. France held out after Hochstedt and Romilly, held out thanks to a strong government, but this government was draining the country's last funds. Since 1700, the number of officials has almost doubled due to the intensive creation of new positions for sale; they overflowed the coin, raised its price, but this only brought benefit to foreigners; the issuance of unpaid notes undermined credit, and meanwhile expenses, which had reached 146 million in 1701, reached 258 million in 1707. They began to take duties on baptisms, marriages, and funerals: the poor began to baptize their children themselves without a priest, they began to get married in secret, and between Meanwhile, in the castles of noble nobles they made counterfeit coins and life at court continued to be luxurious.

The famous Vauban published a book in 1707 in which he proposed a plan for the necessary financial reforms. The book was found outrageous, the fifty-year service of a man whose name was known to every educated person in Europe was forgotten, and Vauban’s book was pilloried; six weeks after this book execution, the author died at the age of 74. But the chief controller Chamillard, not seeing any possibility of conducting business at enormous military costs, resigned from his position. In trouble, they called in his place his nephew Colbert Desmarais, who had been out of favor for twenty years. Entrusting Demarais with a new position, the king told him: “I will be grateful to you if you can find some remedy, and I will not be surprised if things get worse and worse day by day.” Desmarais used desperate means to obtain money to continue the war; he doubled duties on the transport of goods by land and along rivers, which dealt a decisive blow to trade.

The money thus obtained was spent on an unhappy campaign: in the north Marlborough again united with Eugene, and complete agreement still reigned between both commanders, while between the French commanders opposed to them - the king's grandson, the Duke of Burgundy, and the Duke Vendôme - complete disagreement reigned. The consequence was that the French were defeated on the Scheldt at Oudenard and lost the main city of French Flanders, Lille, fortified by Vauban. This was accompanied by a physical disaster: at the beginning of 1709, terrible colds came throughout Europe, not excluding the South; the sea froze off the coast of France, almost all the fruit trees died, the strongest tree trunks and stones cracked; courts, theaters, offices were locked, business and pleasure stopped; Poor people with their entire families froze to death in their huts. The cold stopped in March; but they knew that the seeds were frozen, there would be no harvest, and the price of bread had risen. In the villages they died of hunger quietly; in the cities there were riots and in the markets they posted obscenities against the government. The mortality rate has doubled compared to ordinary years, the loss of livestock has not been compensated even in fifty years.

In March 1709, Louis XIV renewed his peace proposal: he agreed that Philip V would receive only Naples and Sicily. But the allies demanded the entire Spanish monarchy for Charles III, did not agree to return Lille and, regarding Germany, demanded a return to the Peace of Westphalia. Louis XIV convened his council, but the advisers answered the question about means of salvation with tears; Louis agreed to the demands of the allies, asked for one Naples for his grandson, and with these proposals the Minister of Foreign Affairs Torcy himself secretly went to Holland. He bowed to Heinsius, Prince Eugene, Marlborough, offered the latter four million - and all in vain: the allies demanded that the grandson of Louis XIV leave Spain in two months, and if he does not do this before the expiration of the specified period, then the French king and the allies will jointly take measures for execution of your contract; French merchant ships should not appear in Spanish overseas possessions, etc. Louis rejected these conditions and sent a circular to the governors, which said: “I am sure that my people themselves will oppose peace on conditions that are equally contrary to justice and the honor of the French name.” Here Louis addressed the people for the first time and met in this ruined and hungry people the most lively sympathy, which made it possible to maintain the honor of the French name.

Particularly offensive in their senselessness were the demands of the allies that he, Louis, who had made such sacrifices for peace, should continue the war to expel his grandson from Spain, and the war was necessary because Philip felt strong in Spain thanks to the disposition of the popular majority and, of course, , under the dictation of his energetic wife and energetic governess, he wrote to his grandfather: “God has placed the Spanish crown on me, and I will keep it until one drop of blood remains in my veins.” Therefore, Louis had the right to say: “It is better for me to wage war With with their enemies than with their children."

But to save France it was necessary to continue its ruin. There were enough people in the army, because peasants and townspeople, fleeing hunger, became soldiers, but besides people, there was nothing else in the army - no bread, no weapons. A French soldier sold his gun so as not to die of hunger; and the allies had everything in abundance; Thus, the hungry had to fight against the well-fed, the well-fed attacked, the hungry defended, and defended well, because Marlborough and Eugene bought the victory at Malplaquet with the loss of more than 20,000 people. But nevertheless, the allies won, and Louis decided to ask for peace again, agreeing to everything, as long as they did not force him to fight again, and to fight with his grandson. In response, the allies demanded that Louis take it upon himself to expel his grandson from Spain.

The English Tories' fight for peace

The war continued. In 1710, Marlborough and Eugene again made several acquisitions in French Flanders. Louis XIV demanded a tenth of the income from all those belonging to the taxable and non-taxable classes; but due to the exhaustion of the country and dishonesty in payment, the treasury received no more than 24 million. Funds for the 1711 campaign were prepared; but the year began with peace negotiations, and this time the peace proposal did not come from France. In January, Abbé Gautier, secret correspondent for the French Foreign Office in London, came to Versailles to see Torcy with the words: “Do you want peace? I have brought you a means of concluding it independently of the Dutch." “Asking the French minister if he wants peace is like asking a patient with a long and dangerous illness if he wants to be cured,” answered Torcy. Gautier had instructions from the English ministry to propose to the French government that it begin negotiations. England will force Holland to finish them.